- Home

- Helena Merriman

Tunnel 29 Page 7

Tunnel 29 Read online

Page 7

15

Valley of the Clueless

September 1961

JOACHIM OPENS HIS window and looks out. The River Elbe stretches below, the bright morning sun glistening on the water, luscious green trees covering its banks. It’s been a month since Joachim drove back from the campsite and saw the barbed wire. Now he’s back at university in Dresden, two hour’s drive south of Berlin.

Looking out over the rooftops, Joachim feels a long way from Berlin and its new concrete Wall, far enough that he can almost ignore it. Almost. Though he’s seen photos of the new Wall, knows how hard it would be to escape over it, now and then Joachim finds himself imagining living on the other side. He could study what he wanted – engineering – rather than Transportation Studies, which he had no interest in. Though he’d got brilliant marks at school, because of his patchy socialist record – in particular, not being part of the Free German Youth – he wasn’t allowed to study what he wanted. He knows he will never amount to much in East Germany. People like him never did.

And he’s heard the rumours, how the party was going after people who’d spent time in West Berlin before the Wall went up. Like a jealous lover punishing an unfaithful partner, the party sent Grenzgänger – people who lived in the East but worked in the West – to work in factories, told teachers who’d worked in West Berlin’s schools they could never teach again, and they barred students who’d studied in West Berlin from universities in the East, forcing them to do grunt work in factories. Now that the Wall was there to cage people in, the party didn’t have to try so hard to win people’s love. Though the party had always taken a tough line with anyone who criticised it, after building the Wall the number of political activists arrested sky-rocketed. In the first half of 1961, 1,500 East Germans were arrested for political crimes. In the second half of that year, after the Wall went up, that number quadrupled to 7,200.

As well as the arrests, the party was spinning the narrative about the Wall. First, they never called it that – a Wall. Instead, in articles that appeared in the party newspaper, Neues Deutschland, Ulbricht called it the antifaschistischer schutzwall – ‘the anti-fascist protection barrier’. This wasn’t a Wall to keep people in, Ulbricht wrote; it was a Wall to keep people out, to protect East Germans from the ‘vermin, spies, saboteurs, human traffickers, prostitutes, spoiled teenage hooligans [who] have been sucking on our… republic like leeches on a healthy body’.

In Ulbricht’s alternative story, he was the protector of East Germany, for it was under constant threat of invasion from the West. The party even funded a film that they released shortly after building the Wall, a film with a title suspiciously similar to a book that came out the year before, written by Ian Fleming – For Your Eyes Only. In the East German film – For Eyes Only – an East German spy discovers an American plot to invade his country. The message in state newspapers, TV and film was clear: West Germany is full of bad people and only the Wall can protect you.

While a few party faithfuls bought this alternative story, felt protected by the new Wall, most didn’t. They had seen the VoPos patrolling the border in their helmets and knee-high black boots, and they’d noticed that their Kalashnikovs didn’t point towards the ‘hooligans and saboteurs’ in the West. They pointed back at them.

Things were changing. Fast. In this newly divided city, everyone was choosing sides, and though Joachim had chosen to stay, he wasn’t sure it was the right decision. He’d just heard that the party had introduced forced conscription: with such a long Wall to protect, they needed more VoPos, and he’d been told he would have to sign up soon. Joachim imagines patrolling the Wall, Kalashnikov at the ready, under orders to shoot anyone who tries to escape. The idea horrifies him.

Until now, his only military experience was two compulsory stints in the reserves during the last two summers, when Joachim spent hours marching in drill practice and running around in field exercises. As the technology whizz-kid, Joachim was put in the communications group, his backpack stuffed with radios. Dressed in a khaki-green uniform, steel helmet wobbling on his head, gas mask strapped to his face, Joachim ran away from imaginary foreign soldiers, threw himself onto the ground to avoid imaginary aircraft, up and down, up and down, until all the bones in his body ached. He’d hated it and found himself getting into heated arguments with senior officers. Until then he’d always been good at toeing the line, but he was finding it harder to bite his tongue. His best friend Manfred was becoming even more belligerent: a few weeks ago he’d refused to swear the oath of allegiance and he’d been kicked out of university.

Joachim looks out over Dresden. Tal der Ahnungslosen they call it – ‘the valley of the clueless’. For in Dresden, unlike East Berlin, it is almost impossible to get a TV or radio signal from West Germany. People who live there are stuck with Deutscher Fernsehfunk, East Germany’s only TV station, famous for its weekly show, Der Schwarze Kanal – ‘The Black Channel’. It begins with an electro-pop theme tune that sounds like the 1980s internet dial-up tone; then, after a title sequence involving an eagle, a plump man with thick-lens, over-size glasses wearing a dull suit and tie appears. His name is Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler and he is here to warn people about the poisonous sewage streaming out of the West through its TV stations. Hence the title – The Black Channel – which is what German plumbers call the sewers. Selecting clips from West German TV, Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler explains in an avuncular tone why it is all filth. With so much air-time, he is now the face of the party, and anyone who hates the party now hates him as much as Walter Ulbricht.

The only way people in Dresden could get away from von Schnitzler and East German TV was by climbing onto their roof and turning their aerial towards the West. But this was dangerous. Ulbricht was determined to stop people in East Germany tuning into news from the West; he knew TV was powerful propaganda. His party tried jamming the signal, but people found it. And so he’d made it a criminal offence to consume Western news: anyone caught doing so could be fined or arrested. And the party always had ways of finding out. If pupils doodled logos of Western TV news stations, teachers would report them and their parents could be arrested. In Dresden, Stasi informants stood at windows with binoculars, scanning the skyline for aerials pointing west. Looking at those aerials, thinking about the people risking jail to watch TV from over the border, Joachim thinks about the years ahead, wondering whether he can keep his head down as the party becomes ever more controlling, taking away his choices, one by one.

Picking up his bag, Joachim sets off for his first class of the day, first walking to the kiosk, where he picks up a newspaper. And there on the front page, he sees it: the article that changes everything. It’s a list of names of everyone in Dresden who’d been caught pointing their aerials towards West Germany, along with photos of their apartments. It’s the first time Joachim has seen anything like it, and as he holds the newspaper, he feels an anger rise up within him. Suddenly he sees himself, a twenty-two-year-old with his whole life ahead of him, living in a country where you can’t say what you want, think what you want or watch what you want. All the things he’d got used to – the compromises, the unwritten rules – now flash up before him, and seeing his life afresh, Joachim doesn’t like what he sees. It’s like one of his home-developed photographs suddenly drained of colour.

Everyone has different breaking points and this is his. And so the Wall forces a decision upon Joachim, as it has for others: people who thought they could cope if they just kept their head down make new calculations. Across East Germany, in the shadow of the Wall, there are awakenings: teenage boys who know the army will soon call on them, daughters who want to feel their mother’s arms around them again, farmers who want to be able to live off their own land, doctors who want a proper career – they express the same fears, and come to the same conclusions that people all over the world have reached time and again, whenever the place they’re living in becomes too much to bear.

They decide to escape.

16

Binoculars

JOACHIM HEARS FOOTSTEPS on the stairs. It’s Manfred, here for their morning’s planning, for the two of them have decided to escape together and they need to find a way out that won’t get them killed. They’ve heard about the escapes at the border, they know people have been jumping the barbed wire, but getting over the new concrete Wall is a different prospect.

They read about the ones who’ve succeeded: the delivery driver who smashed his van through the Wall, the couple with their baby who broke through the Wall in a seven-tonne dump truck full of gravel. But with every escape, the VoPos had got smarter: they sealed holes in the Wall, added lookout posts, dog runs, anti-vehicle ditches, then created a no-man’s-land, an area that stretched for a hundred metres on both sides of the barrier. It was under the cover of darkness that most tried their luck; searchlights would rake the Wall, then there were screams and shouts from people who disappeared into the night.

Some of the most extraordinary escapes happened on a mile-long street called Bernauer Strasse, a street now famous all over the world as the Berlin Wall ran right down the middle of it. The living areas of the houses were in the East, pavements in the West. To escape, all residents had to do was walk out of their front door. Then the VoPos came, forced thousands out of these houses at gunpoint and bricked up the windows and doors.

Only a handful of residents were allowed to stay – those on the top floors. Their windows looked out into West Berlin and they would wave down to friends and family on the pavement, throwing out handwritten notes and presents. One afternoon, a bride in a white lace dress and her groom came to the pavement in the West to get married, the parents of the bride watching from the window above, lowering flowers in a basket. Then there were the teenagers who appeared at the windows, holding up signs for their girlfriends in West Berlin; and parents who held up two-day-old babies for their grandparents.

But soon all these things were forbidden. Walter Ulbricht released new rules criminalising any kind of contact over the Wall, including chatting and waving, and life in those wall-side apartments got bleaker. As border guards patrolled the buildings, monitoring what people were doing at their windows, those inside became more desperate, so desperate that some decided if they couldn’t escape through the front door, they would take a different route.

Windows on the third and fourth floors would open, windows that hadn’t been bricked up as the border guards thought no one would be crazy enough to escape out of them, and from those windows people would emerge. Tottering on window ledges, some slid down bedsheets, others leapt into the air, hoping that people on the pavement in the West would catch them. Sometimes, pieces of paper would flutter down from the windows onto which were scrawled floor numbers, window numbers and a date and time. At the appointed hour, on the appointed day, firemen in West Berlin would huddle under the window, holding heavy-duty fire-nets ready to catch whoever jumped.

Seventy-seven-year-old Frieda Schulze decided to jump on 24 September. That day, she threw a few precious things – including her cat – out of the window, then climbed onto the window sill. News crews from the West were filming, and in the footage you see Frieda wearing a long black dress, hovering out of her window, her short white hair glinting in the sun.

Then suddenly you see them – a pair of arms grabbing her from the inside. Border guards have broken into Frieda’s apartment and they yank her arms, trying to pull her back in, while people on the street below jump up and grab her legs.

The East and the West are fighting over one woman.

After a few minutes, Frieda’s shoe falls off and she dangles by one arm, looking as though she might snap. A border guard throws a tear gas canister out of the window, but the people below don’t give up. Choking on smoke, throats burning, they pull on Frieda’s legs, harder and harder, until suddenly, her arm comes loose and she falls into the net to the sound of cheering and whooping. The border guards pull back from the window. They’d lost this one.

It was also on Bernauer Strasse that the first death at the Wall was recorded. Ida Siekmann lived in one of the apartments there; she was fifty-eight years old and before the Wall went up, she’d go into the West every week to see her sister. Photos show a woman with a soft, plump face, no hard edges. After the Wall was built, Ida was cut off from her sister and she knew she might never see her again. The day VoPos bricked up the door to her building, it all became too much. Ida threw her bedding and a few belongings out of the window of her third-floor apartment and jumped.

There was no net.

She died on the way to hospital one day before her birthday. An East German police report noted her death in a couple of lines, adding, ‘the blood stain was covered up with sand’. A few days later, a makeshift memorial appeared at the spot where Ida died, her name carved into a piece of wood. Next to it, a garland of flowers.

Though the police wrote meticulous reports of escape attempts, they tried to keep deaths out of the news. They didn’t want the bad publicity, particularly once the killings began. On 22 August, the party gave new orders to border guards: from now on, anyone ‘violating the laws of the GDR could be called to order, if necessary by the use of weapons’. If you were caught trying to escape, you could be shot. Two days later, the border guards showed they were following orders.

Günter Litfin was a twenty-four-year-old tailor with brown eyes and a mass of dark, curly hair. He lived in East Berlin, but worked in the West as a costume maker for the theatre. He was doing well; he’d made beautiful costumes for some of the greatest actresses of the time and he planned to move to West Berlin. When the Wall went up, Günter lost not only his job, but the whole life he’d created.

Just after 4 p.m. on 24 August, Günter crept onto the bank of the River Spree. The river was a popular escape route; it was only thirty metres to the other side – hundreds had escaped this way, including a couple who’d swum across, pushing their three-year-old in a bathtub.

But Günter wasn’t as lucky. TraPos – (transport police) – spotted him before he even got into the water, shouting at him to stop, but he carried on, running towards a jetty as the TraPos fired warning shots. Leaping into the water, Günter swam frantically towards the West as the TraPos fired their machine-guns, bullets peppering the water, yet still he kept going, and he’d almost made it to the other side when a bullet found him. Ducking under the water, Günter tried to hide, but he had to come up for air eventually, and when he did, gasping a panicked breath and raising his hands in a kind of surrender, the police fired their final shot, the bullet piercing the back of his head.

Günter sank. His body was pulled out three hours later, by which time hundreds of West Berliners had heard what was happening and had raced down to the river, watching and screaming as his body was fished out. The next day, the story appeared in West Berlin’s newspapers:

ULBRICHT’S HUMAN HUNTERS HAVE BECOME MURDERERS

The party knew they couldn’t keep this story out of the news in the East, but they could spin it. They ran an article in their party newspaper, Neues Deutschland, describing Günter as a homosexual criminal, then used their favourite propagandist, Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler, host of The Black Channel, to disparage Günter on air. A few days later, secret police searched Günter’s mother’s apartment and interrogated his brother, but didn’t tell them what had happened. His family only found out he’d been killed from West Berlin TV. At the funeral, hundreds of people turned up, people who didn’t even know Günter, and they watched as his brother, Jürgen, leapt into his grave and broke open the coffin to see Günter one last time.

The party followed the same procedure for most deaths at the Wall. They never admitted their shoot-to-kill policy, so these deaths were awkward events that had to be managed. They rarely allowed families to see the bodies, though sometimes the party would fund a funeral, using money they’d found in the dead escapee’s pocket. This wasn’t out of charity, but because funerals were good opportunities for intelligence gathering. Whil

e the family mourned at the graveside, secret police would lurk in the background, making notes of future trouble-makers. VoPos killed on duty were treated very differently: they were given funerals with full military honours, streets and schools named after them. But the families of those killed while trying to escape soon found their own way to mark their grief: they wrote the names of their dead on pieces of paper, wrapped them onto the barbed wire and erected small white crosses where they’d been killed.

Joachim and Manfred had seen those small white crosses, knew that if their escape went wrong, there could be a wooden cross for them. They had to find a way out, fast. It was already mid-September, one month and four killings since the barbed wire went up. Every week they waited, it would get harder.

Joachim walks over to the TV and turns it on. There’s a programme on West Berlin TV that shows different sections of the border, updating viewers on the latest places to be closed off. This is how Joachim and Manfred begin each morning’s research: sitting up close to the TV, they watch the programme closely, looking for places they might sneak over. When they see something promising, they circle street names or squares on maps in front of them. But every day, the number of places is whittled down as new barriers appear, new parts of the border sealed off.

The following day, Joachim and Manfred jump on bicycles and cycle to the places they’ve identified to check them out: quiet spots in corners of East Berlin, places they think they might sneak through. But none look safe, too many VoPos around. And they can’t swim through the river, as VoPos have strung barbed wire under the water.

Back home, they puzzle over the maps again. Joachim follows streets and squares and train lines with his eyes, looking for inspiration. Then it comes to him: so far they’ve been looking for escape routes inside East Berlin, but maybe there’s a better chance of escaping outside the city.

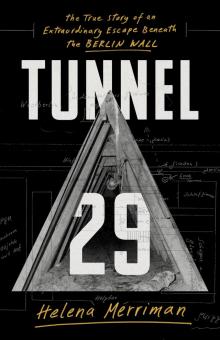

Tunnel 29

Tunnel 29