- Home

- Helena Merriman

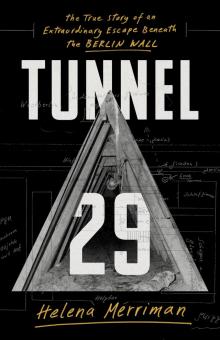

Tunnel 29 Page 5

Tunnel 29 Read online

Page 5

Like the Soviet KGB, the point of East Germany’s secret police was to protect the party from the people, and the party desperately felt it needed protecting – not just from bridge-bombing activists, but from ordinary people too. The party never recovered from the shock of the 1953 uprising that Joachim had been part of. They blamed the secret police for not predicting it and were determined that nothing like that ever happen again.

In the early days, East Germany’s secret police had been a crude, brutal operation; if you made trouble, they’d arrest you, there might be a show trial with forced confessions, possibly a death sentence. But when Erich Mielke took over, he wanted to do things differently. Instead of coming for you after you’d committed a crime, his police would come for you the moment you started plotting. It was the same philosophy behind the machines in the Tom Cruise sci-fi film, Minority Report, where police use futuristic technology to catch criminals before they committed a crime. In 1950s East Germany though, without that technology, there was only one way to anticipate crimes: through information.

And so began the most ambitious project in state surveillance. The Stasi wanted to know everything about everyone: where you worked, what you read, what you worried about, who you were married to, who you were sleeping with, what you dreamt of, even what you smelt like.

There’s an old East German joke: why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? Because you get in the car and they already know your name and where you live. Information was everything to the Stasi and they became the best information hunters around, buying equipment from the West and reverse engineering it so they could make listening devices and spy cameras. The Stasi would come up with a reason for you to be out of your apartment – a doctor’s appointment perhaps – then they would break in with a small team, taking polaroid pictures so that they could recreate your flat afterwards, searching your home, looking for anything incriminating: letters, foreign money, dissident poetry. They’d hide cameras and microphones in your telephones and light fittings so they could record every hour of your waking and sleeping life. Thousands of those recordings still exist in the archives today: you can hear children’s parties, lovers’ arguments, sex, loo visits, all of life in its beauty, mundanity and absurdity recorded, catalogued and filed.

A word was soon invented to describe this mass surveillance: flächendeckend. It translates as ‘covering all areas’. And all areas were covered, as the Stasi soon had a network of spies covering the entire country. There were the Stasi ‘mailmen’ from Department M who’d sit in secret rooms in every post office in the country, X-raying and steaming open thousands of letters. There were the officials in Department 26 who eavesdropped on phone calls. Find enough dirt and they’d come for you at work, arresting you in front of colleagues to remind people they were watching. Once arrested, you would be taken to the Stasi headquarters in the district of Lichtenberg in East Berlin. The House of One Thousand Eyes – that’s what people called it.

At first, the Stasi headquarters was just a small collection of offices on Magdalenenstrasse, somewhere to house the fledgling secret police force. Then, over the years, it grew into a concrete fortress, swallowing up the streets and houses around it like a black hole. The windows all had shutters, the concrete walls bristled with security cameras and the entrance was obscured by thick steel so that no one could see in. Inside, the compound housed every activity of secret policing imaginable – not only interrogation rooms, prisons, a training academy and thousands of offices, but also cafes, shops with luxury products imported from the West, a hospital and even a hairdressing salon, so that, once at work, Stasi employees would never have to leave. No popping out for a sandwich in your lunch-break.

Right at the heart of it, through the maze of linoleum corridors, sat Erich Mielke, the Stasi’s Wizard of Oz, masterminding everything from his study, a bust of Lenin watching over him. From here, Erich Mielke ran the Stasi’s operations, as well as its universities, even its football team, BFC Dynamo, which he was obsessed with, rigging matches with Stasi-referees.

Of course, anyone brought here to be questioned did not see any of this. They were taken straight down to the Hundekeller – ‘the dogs’ cellar’. It’s the name prisoners gave to the interrogation rooms where people would disappear, never seen again. There are horrifying stories of the physical and sexual torture that went on there in the 1950s – prisoners kept in solitary confinement in cells with no windows before secret trials in which they might be sentenced to death, or hard labour in prisons like Bautzen, where the conditions were so appalling that around sixteen thousand died.

But the Stasi were also pioneering more sophisticated tactics, such as zersetzung – ‘decomposition’. This was a subtle art the Stasi perfected and taught at the Stasi Academy, of applying continuous pressure to people they didn’t like, so they would feel as though their lives were falling apart. The Stasi had oversight over most jobs, not just in the army or government, but in universities or factories. If they didn’t like you, a simple phone call to your boss or partner would end your career, break your marriage, until you felt completely powerless, leading some to commit suicide. The Stasi pursued this strategy of zersetzung so effectively that it became impossible to trust anyone: you never knew who was one of them, so you would imagine the Stasi were everywhere, listening in on every phone call (when, of course, they didn’t have the manpower for that), opening every letter. And so East Germany became a country of hushed voices, suspicious looks and self-censorship.

Stasi agents had been out on the streets, shooting protesters during the 1953 uprising that Joachim had been part of. And that year, for those who’d had enough of feeling afraid, who were no longer brave enough to sing songs in the street and march, there was only one option: to leave.

In 1953, the year of the uprising, 330,000 people left East Germany. And every year people kept leaving. Soon, Walter Ulbricht was so worried that he made leaving East Germany a crime, inventing a new word to describe it: Republikflucht – ‘flight from the republic’. Anyone caught crossing the border unauthorised was arrested, put on trial, thrown in prison.

Still, they kept leaving.

Bus drivers leave, nurses leave, engineers, dentists and lawyers all leave. Soon, there are towns in East Germany without a single doctor or teacher. Then there are the more embarrassing defections: the Soviet soldiers, the government officials, and then, in 1961, in a particularly high-profile humiliation, Marlene Schmidt, a beautiful, blonde engineer who’d escaped out of the East – described in a West German newspaper as having an ‘engineer’s brain on a Botticelli figure’ – became Miss Universe. After she’d minced down a catwalk in Miami Beach in her Miss Universe crown, in an event broadcast all over the world, including East Germany, Time magazine published a piece expressing surprise that ‘the East German border guards failed to spot lissome, 5-ft. 8-in. Marlene… The West had no difficulty.’

Walter Ulbricht discovers that there is something worse than his country being an international pariah: East Germany is becoming a joke.

By 1961, East Germany has lost three million people – around a fifth of its population. That year, each month, the numbers increase: in June, 20,000 leave; 30,000 in July. Soon, the deluge of people leaving becomes so great that a new word is coined to describe it: torschlusspanik – ‘the rush to get out before the door slams shut’.

And that now is Walter Ulbricht’s dilemma: how can he not only slam that door, but bolt it so that no one else can escape? There is already a 900-mile barbed-wire fence running the length of East Germany to stop people escaping into the West, but all they have to do is travel to East Berlin and, from there, they can hop on a train into West Berlin. The problem, he knows, is East Berlin. It’s an escape hatch.

And so Walter Ulbricht comes up with a plan: if he can’t persuade people to stay in the East, he will build a wall and lock them in. But when Walter Ulbricht puts his wall-plan to his Soviet commissars, they are appalled: it will be a PR disaster! H

ow can they persuade the world that communism is better than capitalism if East Germany has to build a wall to stop people escaping the so-called communist paradise? Instead, the Soviet government’s instructions to Walter Ulbricht are surprising: if you want to stop people leaving, make their lives better. After all, the Soviet Union was now opening up, beginning to reform, yet here was East Germany continuing down the Stalinist path more obsessively than any other country in the Soviet empire.

But Walter Ulbricht does not introduce reforms or change direction. And later that year, as East Germany continues to haemorrhage its youngest and brightest, and as Walter Ulbricht badgers the Soviet government, sending maps outlining the route of the wall, the Soviet Union caves in.

Walter Ulbricht will get his wall.

10

Operation Rose

Saturday 12 August 1961

IT’S DUSK IN East Berlin. The streets are covered in streamers and pastel splodges of ice-cream after the annual children’s fair. High on sugar, children have been allowed to stay out late and they crane their necks to the sky, watching fireworks.

As the rockets whizz and pop above them, further east, in the People’s Army headquarters, the country’s most senior military commanders are gorging on a luxurious buffet. It’s all the food you can’t usually get in East Germany – sausage, veal, smoked salmon, caviar. The commanders have no idea what’s brought this on, what’s about to happen. All they’ve heard is that there’s a secret operation happening that night. At 8 p.m. exactly, the commanders open sealed envelopes and read detailed instructions, setting out what must happen every hour of the night ahead.

Meanwhile, the mastermind of all this, Walter Ulbricht, is hosting a garden party. It’s out of character – he’s serious, terrible at small talk and doesn’t have friends, but here he is, surrounded by his ministers in his woodland retreat. There’s music, a Soviet comedy film plays in the background – an attempt at light entertainment – but it’s awkward. No one knows why they’re here and they can see soldiers skulking in the birch trees.

After supper, at around 10 p.m., as hundreds of tanks and armoured personnel carriers rumble towards East Berlin, ready to catch anyone who might escape, Walter Ulbricht directs his guests into a room and that’s when he tells them: he’s about to close the border between East and West Berlin. If anyone wanted to stop him, warn friends or even escape, it’s too late. They’re locked in. Everything is set.

Operation Rose can begin.

It starts with the street lights.

At 1 a.m. they switch them off. They don’t want anyone to see what’s about to happen. Tens of thousands of soldiers then move into position, forming a circle around West Berlin so there can be no last-minute escapes. It takes half an hour.

Now the construction starts. Walter Ulbricht has delegated that to his most trusted units: his border police, the riot police, ordinary police, secret police, and, finally, 12,000 members of the Betriebskampfgruppen – a militia of specially trained factory workers. Ulbricht has thought of every detail: how many men to have at each crossing point, how much ammunition each gets – enough to scare people off but not so much that things spin out of control.

Trucks drive towards the crossing points, depositing soldiers armed with machine-guns who crouch on the streets, weapons pointing towards the West. Behind them, a second group of soldiers creep down from the trucks, pulling out giant coils of barbed wire.

There’s 150 tons of it, bought secretly over the past few weeks from manufacturers in West Germany and even Britain, stockpiled by police units who had no idea what they were keeping it for. Next, the soldiers bring out wooden posts and then, using steel rods, they unfurl the barbed wire, stringing it between those posts, sealing the crossing points at the border.

They begin at Potsdamer Platz, the busiest crossing between East and West Berlin. From there, the soldiers move to other checkpoints, ensuring the barbed-wire fence follows the border exactly, not edging a millimetre into the West: they don’t want to provoke war. And so the barbed wire cuts through parks, playgrounds, cemeteries, squares, not stopping for anything. There are no nasty surprises, nothing the soldiers can’t handle. Every inch of the twenty-seven-mile-long internal border and the sixty-nine-mile border separating West Berlin from the East German countryside has been mapped. They know exactly what’s required.

At 1.30 a.m., armed units shut down all public transport that leads to the West. They split train tracks and seal train stations, under and above ground. It’s hard work, but the night is quiet. Walter Ulbricht has chosen the perfect time for this operation – a Sunday morning in the height of summer when many East Berliners, like Joachim, are on holiday. Ulbricht knew the success of his operation depended on surprise. He didn’t want messiness, anyone trying to stop them as they sealed the city.

By 6 a.m. on Sunday 13 August, the soldiers have closed off 193 streets, 68 crossing points and 12 train stations.

Their work is done.

11

Mousetrap

DAWN ON SUNDAY 13 August and it’s the city’s workers who are up first. Straight away they know something’s happened. In the half-light they see men in uniforms on the streets – soldiers, police, border guards and, looming behind them, the hulking outline of tanks. Then, at the border, they see it: the barbed wire.

At first, they don’t know what to think. Wandering along the barbed wire, they try to work out where it’s come from, where it’s going. As others wake and stumble towards the border, a group of men gathers, shouting at the border guards, asking what’s happened, getting angrier and angrier until the border guards turn and shoot tear gas. Coughing and spluttering in the chemical smoke, their eyes streaming, the men run away.

Then the vans appear. Weaving through the streets, East German officials inside broadcast over loudspeakers the news that the border is closed.

Panic sets in.

Parents pack suitcases and drag children to railway stations, hoping that trains might still be running to West Berlin. Cramming on trains, they take the same journey that Joachim had done many times as a boy, but at Friedrichstrasse station, instead of passing through the border, they hear a new announcement: ‘Der Zug endet hier’ – ‘The train ends here’. Then, onto the trains come the VoPos (short for Volkspolizei – ‘People’s Police’, referring to the East German armed forces who defend the border). The VoPos herd everyone off the train and onto the platform, which is now heaving with people. Sitting on suitcases, women, children and grown men are crying at the unreality of it all. One elderly lady walks up to a VoPo and asks when the next train will go to West Berlin. He turns and laughs. ‘That is all over now,’ he tells her, with a sneer. ‘You are all sitting in a mousetrap.’

Back at the barbed wire, thousands of East Berliners are standing in a daze – mothers with babies perched on their hips, children holding teddies, groups of lanky teenagers. Some ask about the Americans; surely they’ll do something – bulldoze the barbed wire with their tanks? But American tanks never come. At one point, a few British jeeps show up, watch for a while, then go home.

On the other side of the border, in West Berlin, young men on motorbikes tear through the city to the Brandenburg Gate where East German soldiers are breaking up the road with jackhammers and pounding in concrete posts. ‘Ulbricht! Murderer!’ they chant, more men joining until there are hundreds, screaming and shouting at the soldiers. Eventually, just as their protest threatens to spiral out of control, West German riot police pull them back.

And it’s then that Berliners realise what the barrier means.

Mothers in East Berlin are now separated from their new-born babies in West Berlin, brothers from sisters; friends, lovers, grandparents, all divided by the barbed wire. Those in East Berlin with telephones at home try calling children or friends in West Berlin, they dial the numbers but—

Nothing.

The phone lines between East and West Berlin have been cut. Walter Ulbricht has thought of everything.<

br />

And so, as evening draws in, East Berliners are reduced to waving: waving from the tops of cars, waving out of apartment windows, white handkerchiefs in their hands. They have no idea if they’ll ever see their parents, their children again.

There are lots of photos from that day, but there’s one that stands out. It’s a mother with her baby, and they’re standing behind the barbed wire in East Berlin. The rest of her family are on the other side and the mother holds her baby high up in outstretched arms so they can see her child, as the barrier between them gets higher and higher.

That night, as the sun goes down, the full horror of it all sets in.

And now, as Joachim and his friends stare at that barbed wire, having driven back from their camping holiday at the beach, a single question presents itself.

Will you try to escape?

12

Snow

FOR JOACHIM, THIS is difficult. He knows all about escapes, how easily they can go wrong. Memories flash up: the horse and cart. The sound of the Red Army. Sitting in the cupboard with his father, feeling safe in his arms. The sight of his father being dragged away. The feeling that his life had become unhinged from something.

Now, fifteen years later, Joachim must decide whether to risk everything again. Standing at the barbed wire, the houses and cars and streetlights of West Berlin just a few metres away, tantalising him with their proximity, Joachim knows he must stay this side of the border. He’s learnt how to function in East Berlin, how to keep his head down and never risk too much. Now, he must just keep going.

Tunnel 29

Tunnel 29